A couple of years ago, in the spring, I stopped using the front door. A bird nest had appeared, a small straw basket tucked into the wisteria pergola on the path at the front of the house. Although robins had been singing in the nearby trees, I was not convinced that it was theirs, that it might hold new eggs. But I hoped, and began detouring each day, on the way to the kitchen or bedroom, to pass near the front door, watching for a red-breasted bird and picturing the soft color of those iconic, blue eggs.

Even after having chickens for decades, I still marvel at the eggs they lay. Many might think only of boring white or brown shells, but they are wonderfully varied: striking whites of meringue or cream, browns of tahini, milk chocolate, dark brown with even darker speckles, and even shades of blue, light green, and olive. I’ve never taken chicken eggs for granted, since on more than one occasion I have had to wait hours for a few more to be laid before I could make a birthday cake for a friend or a frittata for dinner. But I also learned to value how they look.

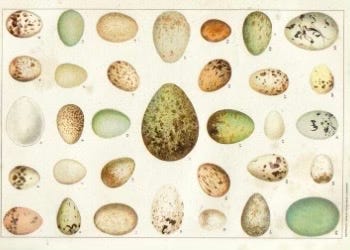

During this particular spring vigilance, I grew even more intrigued about bird eggs and discovered Mark E. Hauber’s The Book of Eggs, an illustrated glossary of bird eggs from around the world. I kept it on the kitchen counter and throughout the day would flip through it, stopping randomly at what was always a stunner: The red egg of the Cetti’s Warbler could, at a glance, be mistaken for a cherry tomato; the grey-brown splotched egg of the Artic Tern seems the origin of military camouflage clothing; Jacanas’ eggs have the black abstract markings of a Jackson Pollack painting; the elegant, crested Tinamou lays a glazed egg the green of pistachio cream; and the eggs of the Bicknell’s Thrush, over a blueish green base, flash light brown speckles, as if chocolate from the Zorzal cacao plantation in the Dominican Republic where the bird winters. So many unique and elegant eggs, laid every day, across the world.

I also found Tim Birkhead’s The Most Perfect Thing—Inside (and Outside) a Bird’s Egg, which tells of the research of the hows and whys of such varied beauty. Amazingly, the colors of all bird eggs are the result of just two pigments—biliverdin, which produces blues and greens, and protoporphyrin, which makes yellows, reds, and browns. Thecolor is applied to the shell in the bird’s uterus, but it is still not completely understood just how the two pigments precisely interact or how more intricate hues and markings are formed. It does seem clear that birds lay uniquely different colored eggs for a variety of reasons. Of course, one is to be recognized as their own. From the sky, some bird species can identify their particular eggs among hundreds of other eggs in similar nests all crammed together on a cliff. But the designs can also be used as disguise, to entice male partners to help incubate the eggs, to announce to predators that they aren’t edible, or even to mimic the color of other birds’ eggs so they can be left to be adopted by another bird.

A bird watcher friend told me that robins are known to eat some of their chicks’ hatched shells for calcium but otherwise immediately remove the shards, releasing them over the edge of the nest to make the long fall to the ground. A week after I first discovered the pergola nest, unmistakable blue shell fragments appeared on the walkway. I picked them up one by one and stared closely at them in my palm. Eventually, I gently set the pieces of blue shell in the green grass.

Thanks for reading. Share widely if you wish

You’re currently a subscriber to Apricot Perigee with Emily Luchetti. As a reminder, the first 100 people who become Founding Members will receive a jar of my homemade jam or flavored caramel sauce as a thank you. (Options for each will be emailed once you sign up!)

Thank you. I am so glad you liked it.

Your words provoke the most beautiful images in my brain. Thank you for sharing your gift!